Thursday, 6 August 2009

Monday, 13 April 2009

How should we deal with the Murray River?

Reproduced below is the full text of the latest Droplet, an irregular email sent out addressing concerns within the Murray River. I encourage people to check out Mike Young's water website. As well as being able to subscribe to Droplet, it is a veritable treasure trove of other useful water and Murray Darling Basin related publications.

(The formatting is copied from the original email)

"More from less: When should river systems be made smaller and managed differently?

“Less is more.” Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

In this Droplet, we discuss the case for reconfiguring rivers and the water-dependent ecosystems associated with them. We envisage a world where the approach to environmental, water quality, stream flow and stream height management is quite different to the way it is today.

Recent announcements that inflows into the River Murray over the last three years were less than half the previous three year minimum that occurred between 1943 and 1946, suggest that it may be time to reconsider the river and the environment we have created through the installation of barrages, locks, weirs and dams. In recent years and as currently configured, evaporative losses have been similar to inflows. Very little water has been available. Irrigators, urban water users and the environment have been doing it tough!

The apparent shift to a drier climatic regime than previously experienced may be here for some time – perhaps for the long term. One way planning for and of coping with such an adverse climate shift is to reconfigure the river – make it smaller, manage it differently and get more flow.

We stress that this is not a new idea. In the last two years, South Australia has closed off over thirty wetlands and moved many irrigation off-take points from backwaters into the main river channel.

Similarly, Murrumbidgee Irrigation has constructed a set of banks across Barren Box Swamp that split it into a number of cells so that water can be stored in parts rather than all of the swamp. This has reduced evaporative losses and has enabled a more diverse environment to be created. A win-win outcome.

Another example is Victoria’s decision to decommission the inefficient and man-made Lake Mokoan water storage and rehabilitate the wetland that once lay under this lake. In the Wakool system in NSW, the idea of threading water through part of the system is under serious consideration. A dynamic management regime has been in place there since 1996.

In a drier regime, is there a smarter way to configure and run a river? Can we get more water to use and better outcomes for the environment from less river?

What would happen if all river infrastructure and all wetlands, waterways and floodways throughout the system were examined carefully with a view to reducing evaporation and using the savings to improve environmental outcomes? Why not water some areas well and leave the fate of the rest to chance.

Pushing the boundary further, in a drier regime, would it make sense to change the way a river is operated? How much should be kept navigable? Should river salinity be allowed to rise in winter on the understanding that it will be lowered in summer?

Why, when so much is being invested in irrigation infrastructure don’t we look at river infrastructure?

Less river?

Scientists are warning that we can expect a much drier regime. As set out in our report, A future-proofed Basin, as it gets drier an increasing proportion of inflows are required just to cover evaporate losses. This unfortunate reality cannot be denied.

A small reduction in mean rainfall, say, 10% can lead to a 70% reduction in the volume of water available for use. In the short term, the system storages can be run down but, ultimately, either the amount of water for evaporative and other system losses needs to be reduced or the amount used for environmental, irrigation and other purposes cut drastically.

One of the simplest ways to reduce losses is to build a bank or control structure so that water can be kept out of an area and evaporative losses reduced permanently. Another way is to construct a bank across a lake and fill part rather than all of the lake.

Benefits and costs

When resources are scarce, the available water needs to be applied in areas where it can make the greatest contribution. When evaporative losses are reduced, more water is available for all forms of use, including over-bank applications to water-dependent ecosystems on either side of a river. Changes like this do, however, come at a cost. A benefit to one person may come at a cost to others. Nearly every part of a river has people who are sentimentally and/or economically attached to it.

Deciding to close off part of a river system may sound a bit like triage – even if it is man-made. In practice, however, this is really about the allocation and use of scarce resources for maximum benefit. Careful research, analysis and evaluation of trade-offs are necessary.

Indices of environmental and other values must be developed and processes established to assist in deciding which parts of the system to keep and which to let go. Careful community engagement and consultation is essential. At the end of the day, one would expect some parts of the system to be kept inundated no matter how dry it gets, some parts to be watered periodically, some parts to be watered only in very wet years and some parts to never be watered again. Some probably never should have been watered.

Smart management of environmental water

In an environment where there is insufficient water to keep all environmental assets going, the usual recommendation is to ensure that all watering decisions complement one another. Diversity and risk reduction, not more of the same is the way to go. Smart environmental managers must be expected to water some parts well rather than all parts poorly. Like farmers, they need to be able to spit forests into two or three areas and should be required to monitor water use carefully.

Timing is also important. If all environmental allocations are held centrally, however, speedy decision making is problematic. In our view, environmental water use will be much more effective if local managers are allowed to manage and given the responsibility to decide when to use water that has been allocated to them, when to sell it, when to carry it forward and when to buy more.

Strategies still need to be developed and considerable co-ordination is necessary, but if smart outcomes are to be achieved, then innovation must be the name of the game. In this brave new world, we should expect environmental managers to be as smart in the use of techniques and technology as irrigators are.

River height and flow management flexibility

Another issue is the management of river height and flow. In regulated river systems, like the River Murray, river height has been kept constant for many years. Most of this system’s locks and weirs were installed between fifty and one hundred years ago. With a change in management regime, many transitional problems can be expected to emerge. As illustrated by recent decisions to lower the river, acid sulphate soil hot spots may emerge and banks may slump.

Recreation and navigation values and irrigation supply access issues need consideration. Town water supply and sewage treatment arrangements may need a rethink. Careful analysis may suggest that when water supplies and inflow are low, some weirs may be better left open. In places where this is done, new water supply arrangements may need to be put in place. In some parts of the system, for example, we suspect that it may be more efficient to pipe water from the river and abandon some of the channel systems and local wetlands dependent upon water previously supplied from these channels.

Dynamic river salinity management

There is an old saying that the secret to pollution is dilution – but dilution requires water. When demand is seasonal, a much more dynamic approach to salinity management may be possible. If the impacts of river salinity are less in winter than in summer, why not allow river salinity to go up and down? If this happened salinity managers would need to be given incentives to manage river salinity and plan when to release salt into the system – as is done in the Hunter River. These managers also need to be made accountable for the groundwater they use. Each salinity interception scheme could be given an entitlement which requires them to keep use within the volumes of water allocated.

Environmental managers would also need to be brought into the management system. At the moment, there are large volumes of salt lying on the surface of water-dependent ecosystems along the sides of the river. As soon as these floodplains receive water again, large volumes of salt will enter the river.

Where to from here?

The first step in thinking about reconfiguring a river system is to search for opportunities to do this. Given the current state of the River Murray system, we think that this opportunity is worth serious consideration. Having scoped and identified the opportunities to close off wetlands, make lakes smaller etc., the next step is to develop the models and decision making tools to enable rational choices to be made. Armed with such information and tools, the last step is to come up with a suite of recommendations about the nature of changes which if made, would make river operation under a drier regime more effective and efficient.

Given the complexity and sensitivity of this task, it may be wise to appoint an independent person to lead a group of people able to commission research and evaluate opportunities in a rational manner and consult widely about ways to re-configure and operate our rivers and the many ecosystems that lie on either side of their banks. Their brief would be to find ways to get more outcomes from a smaller but better managed river system.

Mike Young, The University of Adelaide,

e-mail: Mike.Young@adelaide.edu.au

Jim McColl, CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems,

e-mail: Jim.McColl@csiro.au

Acknowledgements

Comments made on earlier drafts by Stuart Bunn, Jim Donaldson, Matthew Durack, Judy Goode, Virginia Hawker, Digby Jacobs, Ian Kowalick, John Radcliffe and Bill Young are acknowledged with appreciation. We also acknowledge the opportunity to discuss this issue with a significant number of irrigators, state administrators and the support of our Project Steering Committee.

References (Access themby clicking on the links embedded in this Droplet.)

A future proofed Basin: A new water management regime for the Murray-Darling Basin

Copyright © 2009 The University of Adelaide.

This work is copyright. It may be reproduced subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of its source. Production of Droplets is supported by Land and Water Australia and CSIRO Water for a Healthy Country. Responsibility remains with the authors."

Labels: environment, Murray Darling Basin, water

Friday, 6 March 2009

Is legalisation the answer?

Illegal drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and heroin should be legalised. Prohibition does not work. It is likely that prohibition makes things worse.

We have seen no real lasting successes in the war on drugs. We have seen phenomenal long-term success in the public health campaigns against tobacco.

Drug abuse should be treated as a health concern, not a criminal matter. Why waste billions on incarcerating those in need of our support? Why not spend the money on better hospitals, better healthcare, and better public health support?

Labels: drugs

Monday, 29 December 2008

What makes a 'chick flick' a 'chick flick'?

So, it hardly seems out of character to devote a post to the ubiquitous chick flick.

I started thinking about this question when I saw the Chick flicks post over at Club Troppo.

As with any categorisation of a movie, book, or play, no description will do justice. The lines between genres are blurry at the best of time and a genre such as 'chick flick' is blurrier than most.

One of the commenters at Club Troppo (NPOV) suggests the wikipedia's definition is reasonable. The definition is "a film designed to appeal to a female target audience".

I think this is a woeful definition that produces significant false positives and false negatives.

By this definition it is likely that Top Gun would be counted as a chick flick, though I doubt many would bill it as such.

In fact the entire wikipedia (which is notably marked as requiring additional citations for verification) seems to miss the point.

I would argue that a much better definition for a chick flick is "a movie that appeals predominantly to female and makes use of a traditionally feminine focus (or foci) such as romance, fashion, exploration of human relationships, and does not make use of a traditionally masculine focus (or foci) such as violence, high-speed chases (or other over-the-top elements of action movies), or sex and an emphasis on dialogue over visuals."

Note that the emphasis should be on the traditional femininity or masculinity of the focus subjects of the film rather than on the specific examples I provided. An exploration of human relationships can be undertaken from a masculine focus, it's just not done as commonly.

I would also like to stress that "chick-flick" and "romantic comedy" are not synonyms as several sites I visited have implied1. Whilst many romantic comedies are chick flicks, not all are (though I must admit I struggle to think of a significant counter-example). Easier to demonstrate is that not all chick flicks are romantic comedies - Life as a House is a notable example. This is not to say that there isn't a substantial amount of overlap between chick flicks and romantic comedies, clearly there is.

I would also like to stress the already-emphasised ands that appear in my definition. Whilst I believe that each is individually a necessary condition for a film to be considered a chick flick, none are sufficient conditions in and of themselves.

On a side note, many of my favourite movies are generally considered chick flicks. I think it has something to do with the writing tending to be better in romantic comedies than action movies. That said, the half of my movie collection that isn't chick flicks are war movies.

Labels: definitions, movies

Friday, 21 November 2008

What's With This Financial Crisis?

I am woefully under-qualified to critique his proposal, but it seems to be relatively sound and to take a much more moderate position than previous theory has.

He attacks market fundamentalism quite strongly as faulty, suggesting that the fundamentalists were deluding themselves. He points out something that has seemed so obvious to me from even a precursory understanding of economics that I have long been dismayed and bewildered that so many otherwise rational economists don't seem to grasp its broad strokes - "Just because regulations and all other forms of governmental interventions have proven to be faulty, it does not follow that markets are perfect."

Indeed it doesn't take much to see that markets are often imperfect. Many, if not most, of the economics courses we can study during our degrees are centred around one form of market failure or another.

Admittedly, governments are rather poor at getting things done.

They're far worse at getting things done well.

In a similar vein to the concerns Soros voices at the end of his piece, I worry that our governments will use this as a rationalisation to impose their own faulty, emotion-blinded ideological approaches to economic management. Though to much to hope for in anything but the most idealistic of fantasies, it would be nice to see a government that acts on the basis of solid data and research rather than the ideological views of its constituent lobbies, special interest groups, and political hacks.

Labels: economics, global financial crisis, ideology

Thursday, 23 October 2008

Can Price Incentives Improve Hybrid Car Markets?

This report was written by myself and Christian Reynolds.

Executive Summary

This report has been commissioned by the South Australian Department of Treasury and Finance to examine the effects of implementing an incentive scheme to reduce the price of petrol-electric hybrid vehicles within the

The report finds that whilst a price incentive will improve HEV demand, difficulties with increasing supply limit the effectiveness of the incentive. Furthermore, it is likely that alternative strategies can provide a more efficient outcome. Thus this report does not recommend the implementation of such a policy.

Introduction

South Australians are increasingly concerned about the environment in general and about climate change in particular. A February 2008 poll conducted by Newspoll found that 57% of South Australians believe that the environment is a very important issue (Newspoll, 2008). In July 2008, 84% of Australians believed that climate change is currently occurring (Newspoll, 2008). Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (specifically carbon dioxide, CO2) have become the focus of substantial controversy, with those that are produced by human activities (most notably the burning of fossil fuels) having increased the concentrations of GHG in the atmosphere far beyond the levels historically experienced – an increase of more than 40% since the beginning of the industrial age (SA 2007 strategic plan. T3.5, p23). The South Australian Government has pledged in its 2007 strategic plan to

“…achieve the Kyoto target by limiting the state’s greenhouse gas emissions to 108% of 1990 levels during 2008-2012, as a first step towards reducing emissions by 60% (to 40% of 1990 levels) by 2050.” (Government of South Australia 2007)

Transportation is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Even excluding emissions arising from electricity generation for public transport (such as electric trams and trains) or from fuel sold to international ships or aircraft, transport accounts for approximately 14% of Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions (Garnaut, 2008). Transport is currently the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases in

More extensive use of the public transport system has been suggested as a way of reducing GHG’s with 25% of the public transport fleet now Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) run buses(Transport SA (b) 2002). The next step to achieving this reduction in GHG’s could be the introduction of a price reduction for petrol-electric hybrid cars to enable the South Australian public to match the public transports systems uptake of GHG reducing technology.

One way that the state government believes it can reduce emissions is through increasing the number of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) being driven. A logical step in achieving the necessary reduction is the introduction of an incentive scheme that reduces the price of gas-electric hybrid vehicles. HEVs also reduce other negative externalities alongside GHGs including air and noise pollution and are more fuel efficient in the long term (Denniss 2003).

The transport industry is also beneficial to the South Australian economy with 118,000 cars produced in 2007 (about 35% of the Australian total), leading to over AU$1.5 billion worth of exports and over 9,500 local jobs (southaustralia.biz 2008). Due to a majority of the hybrid cards being manufactured overseas there must be some consideration given to the survival of local South Australian industry. The Victorian automotive industry has with the Victorian and Commonwealth Governments started ‘the Green Car Innovation Fund’, a scheme worth AU$500 million (Office of the Prime Minister 2008). This fund will operate over five years from 2011 and aims to help the Australian automotive industry develop and manufacture low-emission vehicles so as to meet the challenge of climate change whilst maintaining critical automotive industry jobs (Carr Kim 2008). The South Australian Government is not currently involved in this fund and no announcements towards becoming involved have been made. Though research and development of HEV-technology is a separate issue it is important to be aware that a majority of HEVs will be manufactured outside of

Population growth and economic growth are expected to have a major impact on the demand for transport in

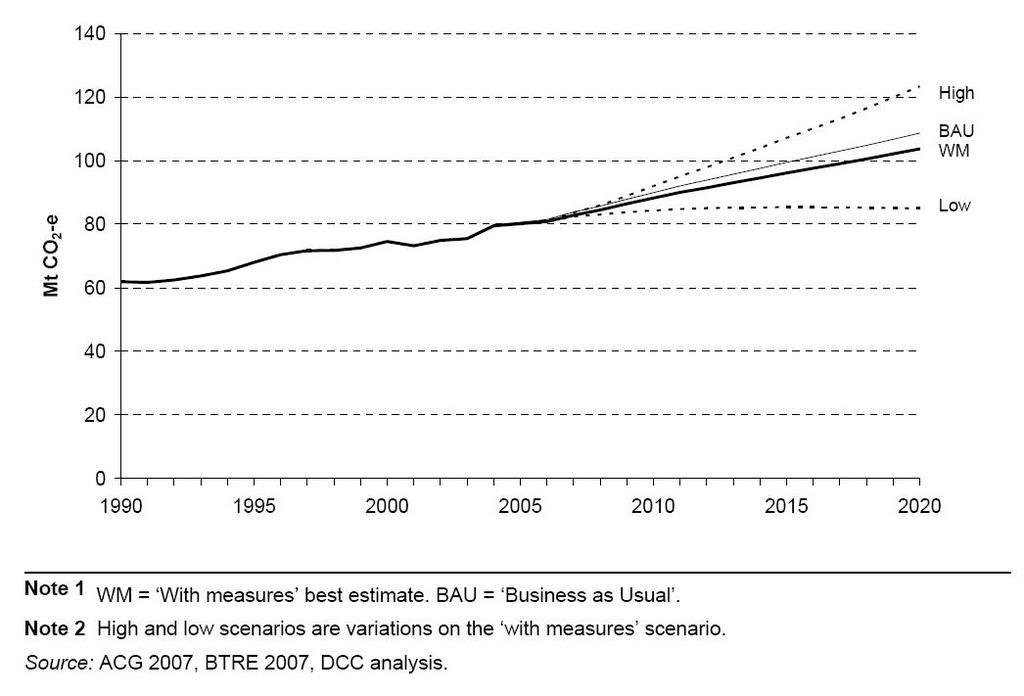

Figure 1 Greenhouse gas emissions for the Australian transport sector

Source: Department of Climate Change. TRANSPORT SECTOR GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS PROJECTIONS 2007, 2008, p5

Theory and Research on Subsidies and Incentive Schemes:

Market forces will generate efficient outcomes only when market conditions include; the existence of perfect information, the absence of market power, the absence of externalities, and the availability of substitutes (Denniss 2003 2-3). The South Australian Government proposed incentive scheme aims to correct the market and reduce the impact of negative externalities – a cost associated with the production/consumption of a good or services which, has not been taken into account by either the producers or consumers - for example GHG and CO2 emissions (Rosen 2005 ch5).

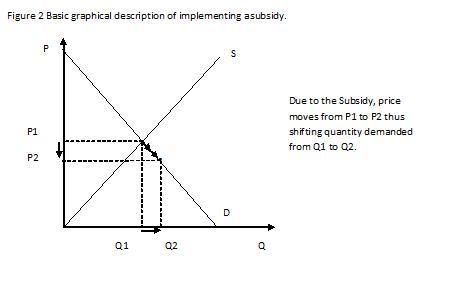

A subsidy is a form of financial assistance paid to a business or economic sector. In this specific case the subsidy in question will be a consumption subsidy given by the South Australian Government to reduce the price of HEVs such that they are more affordable to consumers and a greater quantity are sold. This theory is demonstrated in Figure 2. This assumes that the only barrier to buying a new car is the price and that there is sufficient supply to meet all new demand.

Subsidies are a direct way of achieving efficient results and previous studies (

As HEVs face lower ongoing operating costs (due to lower fuel costs for the same use) (Dowling,2007) the incentive does not need to be as large as might be expected. This assumes that the consumer is both rational and long sighted. Gleisner (2006 84-85) gives the example of a NZ$7000 subsidy for the purchase of the hybrid Toyota Prius resulting in a cost differential of NZ$1270, in favour of Prius purchasers over a ten year period.

A difficulty with the basic model described above in this scenario is the unusual nature of the supply side. Many of the hybrid car manufactures make a loss producing HEV’s (Michaels 2001). Thus the quantity of these vehicles produced remains capped by the manufacturers. In the Australian market there are two dominant HEVs – the Honda Civic and the Toyota Prius. The cheaper of the two is the Honda Civic with a cap of 80 per month sold in the Australian market. The Toyota Prius is also under supply control with caps in place(Michaels 2001). Thus the question arises - will the subsidy have any effect beyond increasing demand?

A further problem with the proposed subsidy is that it does not affect behavioural patterns beyond encouraging the purchase of a more fuel efficient car. It will have no effect on how much, where and how the car is driven. This could result in more severe externalities if the consumers are not responsible drivers (through the consumers producing more emissions through longer drives, more noise and increased petrol consumption due to bad driving technique and habits) (Gleisner 2006 84-5).

Thus there is no guarantee that this subsidy will lower emissions. It is likely that an emissions reduction would occur however given the minuscule supply of HEVs, it is unlikely to be a significant reduction

Management Options for the Incentive Scheme

There are a number of variables to consider in the implementation of an incentive scheme for HEVs.

Gallagher and Muehlegger (2008) found that sales tax incentives were more effective in increasing HEV sales than income tax credit. This is likely due to the delayed nature of the income tax credit, thereby requiring the consumer to have the rebate amount available prior to purchase. Whereas a sales tax credit may be readily applied at the point of purchase and thus effectively reduces the price of the HEV immediately.

Unfortunately, tax credits are not an immediately viable option within

An alternative is to provide an after-purchase rebate which could be applied for by providing proof of purchase of a qualifying vehicle. A notable difference to this system is that a tax credit is limited in total cost to the government by the amount of tax that the consumer is actually paying, whereas the full amount of a rebate would be payable in all cases. Whilst this may cost the South Australian Government more (assuming equally sized rebates) it is likely that the effect of such a rebate would be greater than an income tax credit (though less than a sales tax credit). This is for two main reasons. Firstly, the dollar value of the rebate will be higher for those consumers who will be paying an amount of tax less than the full-value of the rebate. Secondly, a system such as this will be more readily understandable by consumers.

An alternative to providing an after-purchase rebate directly to consumers would be a contribution towards the purchase price of the vehicle which would be paid at the time of purchase directly to the supplier. This would effectively reduce the up-front price of the vehicle for the consumer, functioning (from an incentives viewpoint) much as a sales tax credit.

As well as considering how the price-incentive is to be applied, it is also necessary to consider the size and variability of the incentive. The United States Federal Government HEV incentive currently pays between US$650 and US$3150 dependent on the fuel economy and emissions for each model of vehicle.

If the purpose of the incentive is to promote the use of environmentally-friendly vehicles and reduce overall GHG emissions, then a structure whereby vehicles with lower emissions and superior fuel economy are more strongly supported would be ideal.

The exact dollar-value of the optimal incentive will be difficult to determine. To promote an efficient market it needs to capture the difference in the external effects of fuel economy and emissions from HEVs and non-hybrid vehicles. It is also important to consider the need to promote adoption of the new technology as the lack of support infrastructure and imperfect consumer information will negatively impact the adoption of HEV technology. The support infrastructure may include a lack of availability of spare parts and appropriately qualified mechanics to maintain the vehicles. Imperfect consumer information can lead consumers to be wary of the new technology and possibly distrust or refuse to utilise such technology.

Alternatives to the HEV Incentive Scheme

It is important to consider the primary goal of increasing HEV use.

We believe that the aim of the State Government is more related to decreasing the negative environmental effects of personal transport than to increase HEV sales or to speed the adoption of HEV technologies. As such, it is important to consider alternative mechanisms for achieving this goal.

The principle advantage of increasing the use of HEVs is the significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. HEVs do still produce GHG emissions and thus still force a negative externality upon society. It is counter-intuitive to reward an action that still produces a negative externality. We believe that it would be more efficient to internalise the cost of the environmental impacts of all vehicles in their operating costs. An obvious way to do this would be through the inclusion of petrol in the Federal Emissions Trading Scheme. This will still lead to a stronger incentive to switch to HEV-technology than currently exists as the increased cost of fuel would have a greater impact on non-hybrid vehicle operating costs than it would on HEV operating costs.

Another alternative would be to partially capture emission costs through vehicle registration fees. As emissions are largely dependent on distance travelled, and registrations costs are fixed by time, this will not be a perfect solution. However, ensuring that less environmentally friendly vehicles will face a higher registration cost now and into the future will provide further (potentially quite strong) incentive to switch towards HEV-technology. A superior option would be to link costs directly to the type and quantity of driving. In part this can be accomplished through increasing the fuel costs, but this fails to capture the differing emissions level of different cars burning the same quantity of fuel under the same conditions. A per-kilometre charge built in to registration fees would overcome this, but is not a practically viable option at this time.

It is important to consider the equity effects of non-rebate based schemes. Access to personal transport is essential in many parts of

Denniss (2003) suggests other ways to reduce the emissions and other forms of transport related pollution that can be undertaken on the state level instead of a cash subsidy:

· Provide free parking to owners of vehicles with a low environmental impact.

· Tax fuel inefficient vehicles or Make petrol more expensive for fuel inefficient vehicles, thus changing the buying and driving behaviour of drivers.

· ‘Cap and trade’ for parking spaces introduced in the CBD and other congested areas.

· Abolish mobile billboards.

· Deregulate the taxi industry to lower prices and increase peak hour taxi numbers.

· Allow public transport authorities to sell a combined lottery-transport ticket, thereby increasing patronage and generating additional funds for investment in new public transport infrastructure.

· Subsidies public transport to a higher rate making it even more inexpensive thus increasing uptake.

Effects of the Incentive Scheme

There are three important effects of the incentive policy to consider:

· Increased usage of HEVs – Assuming that HEVs are replacing non-hybrid vehicles (as opposed to being used alongside), this will reduce total emissions. This may also assist in the adoption of HEV-technology, both through increasing research and development incentives for car-manufacturers and through providing advantages to those aspects of adoption dependent on network effects. This will be minimal in absolute terms due to the minuscule nature of the current HEV market and the lack of scope for short-term expansion of supply.

· Financial Costs to the South Australian Government – The State Government will face the full dollar-value cost of the incentive program. Though this may be offset by the decreased externalities associated with transport. This is likely to be a small amount given the miniscule size of the HEV market at present.

· Potential Impact on South Australian Car Manufacturers – Currently, no HEVs are manufactured within

Conclusion and Final Recommendation

An incentive scheme based on a rebate is only likely to lead to a small increase in HEV sales. Gallagher and Muehlegger (2008) found that tax incentives were associated with only 6% of US high-economy hybrid sales from 2000 to 2006.

The effect of petrol prices is likely to put further pressure on HEVs potentially resulting in more rebates being provided whilst not necessarily having a large effect. In the presence of other greenhouse management strategies – such as a national Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – it is likely that an incentive to switch towards HEVs will already exist in a far stronger form than a likely rebate could provide and without imposing a direct cost on the SA Government. From an economic theory standpoint, the main aim of an incentive scheme would be to remove the externality-driven price discrepancies. This would be more efficiently captured by including the emissions in the final lifetime price of the vehicle, likely by increasing the operating costs of those vehicles that are high emitters of greenhouse gases. Although one must consider the important equity issues that may arise through such a scheme.

One can argue that the need to promote a faster adoption of HEV technology and the supporting networks it requires (such as the presence of sufficient qualified mechanics) is a market failure best overcome through a price subsidy scheme.

If the goal is solely to reduce greenhouse emissions from the transport sector, then it is worth considering applying incentive-modifying policies to that sector as a whole rather than to select portions of the sector. This could be accomplished in a number of ways, including differential vehicle registration costs dependent on greenhouse emissions and fuel economy, or through capturing the full cost of greenhouse emissions in the cost of purchasing and maintaining a vehicle – for example, an ETS that incorporates fuel costs, or a carbon tax that is applied to fuels.

We would recommend that the South Australian Government exercise caution in the implementation of an incentive scheme for HEVs. It is likely that without significant improvements on the supply side, the subsidy would have minimal impact. Furthermore, the implementation of policies that internalise the cost of the GHG emissions are likely to increase the demand for HEV’s well beyond already insufficient supply capacities. It is our recommendation that the South Australian Government does not implement this policy but instead pursues the wide-spread internalisation of GHG emission sources not covered by the preposed federal emissions trading scheme whilst lobbying for and supporting a strong, effective and comprehensive federal ETS.

Reference List

Department of Climate Change. (2008)Transport sector greenhouse gas emissions projections 2007, Commonwealth of Australia

Dowling Josh(2007) Hybrid cars the go as fuel price rockets, The Sun-Herald, June 10,

Gallagher,

Garnaut,

Government of

Newspoll (2008) 20/02/2008 – Importance and Best Party to Handle Major Issues, http://www.newspoll.com.au/image_uploads/0205%20Issues%2020-2-08.pdf [Last accessed on 13/10/2008]

Newspoll (2008) 29/07/2008 Climate Change, http://www.newspoll.com.au/image_uploads/0708%20Climate%20Change%2029-07-08.pdf [Last accessed on 13/10/2008]

Office of the Prime Minister(2008), , Joint Press Conference with Minister for Industry, Kim Carr and Premier of Victoria John Brumby, Interview, Toyota Motor Corporation, Altona,

Rosen,

southaustralia.biz,(2008) Investing in SA – Automotive (online)

Transport SA (a)(2002)What are Greenhouse Gases? (online)

Another Shameless Plug

I will continue to post here at Integrated Questions, but I now plan to update at Divided Answers two to three times a week and once a week over at Imaginary Ripples. Integrated Questions will get updated when I have the time and inclination to write a long and considered essay on a topic of some importance - or, as you will see shortly, when my studies compel me to do so.

Enjoy, and as is too often the norm now, ignore the more.