The following is a mock consultancy report prepared by myself and a fellow class-mate as part of the Resource & Environmental Economics III course. The mock report was prepared for (the imaginary version of) the South Australian Department of Treasury and Finance as

This report was written by myself and Christian Reynolds.

Executive Summary

This report has been commissioned by the South Australian Department of Treasury and Finance to examine the effects of implementing an incentive scheme to reduce the price of petrol-electric hybrid vehicles within the South Australia. This report will examine this policy issue, discuss relevant theory and research, the effects of such a policy, various management options, alternatives to the policy, and provide a final recommendation.

The report finds that whilst a price incentive will improve HEV demand, difficulties with increasing supply limit the effectiveness of the incentive. Furthermore, it is likely that alternative strategies can provide a more efficient outcome. Thus this report does not recommend the implementation of such a policy.

Introduction

South Australians are increasingly concerned about the environment in general and about climate change in particular. A February 2008 poll conducted by Newspoll found that 57% of South Australians believe that the environment is a very important issue (Newspoll, 2008). In July 2008, 84% of Australians believed that climate change is currently occurring (Newspoll, 2008). Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (specifically carbon dioxide, CO2) have become the focus of substantial controversy, with those that are produced by human activities (most notably the burning of fossil fuels) having increased the concentrations of GHG in the atmosphere far beyond the levels historically experienced – an increase of more than 40% since the beginning of the industrial age (SA 2007 strategic plan. T3.5, p23). The South Australian Government has pledged in its 2007 strategic plan to

“…achieve the Kyoto target by limiting the state’s greenhouse gas emissions to 108% of 1990 levels during 2008-2012, as a first step towards reducing emissions by 60% (to 40% of 1990 levels) by 2050.” (Government of South Australia 2007)

Transportation is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Even excluding emissions arising from electricity generation for public transport (such as electric trams and trains) or from fuel sold to international ships or aircraft, transport accounts for approximately 14% of Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions (Garnaut, 2008). Transport is currently the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases in Australia (Transport SA (a) 2002), with over 45556 Gigagrams of direct CO2 equivalent being produced in 2004 by cars alone (Department of Climate Change 2008). As such a decrease in transport-related emissions must form a critical part of South Australia’s climate change response.

More extensive use of the public transport system has been suggested as a way of reducing GHG’s with 25% of the public transport fleet now Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) run buses(Transport SA (b) 2002). The next step to achieving this reduction in GHG’s could be the introduction of a price reduction for petrol-electric hybrid cars to enable the South Australian public to match the public transports systems uptake of GHG reducing technology.

One way that the state government believes it can reduce emissions is through increasing the number of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) being driven. A logical step in achieving the necessary reduction is the introduction of an incentive scheme that reduces the price of gas-electric hybrid vehicles. HEVs also reduce other negative externalities alongside GHGs including air and noise pollution and are more fuel efficient in the long term (Denniss 2003).

The transport industry is also beneficial to the South Australian economy with 118,000 cars produced in 2007 (about 35% of the Australian total), leading to over AU$1.5 billion worth of exports and over 9,500 local jobs (southaustralia.biz 2008). Due to a majority of the hybrid cards being manufactured overseas there must be some consideration given to the survival of local South Australian industry. The Victorian automotive industry has with the Victorian and Commonwealth Governments started ‘the Green Car Innovation Fund’, a scheme worth AU$500 million (Office of the Prime Minister 2008). This fund will operate over five years from 2011 and aims to help the Australian automotive industry develop and manufacture low-emission vehicles so as to meet the challenge of climate change whilst maintaining critical automotive industry jobs (Carr Kim 2008). The South Australian Government is not currently involved in this fund and no announcements towards becoming involved have been made. Though research and development of HEV-technology is a separate issue it is important to be aware that a majority of HEVs will be manufactured outside of South Australia and are likely to be imported from overseas.

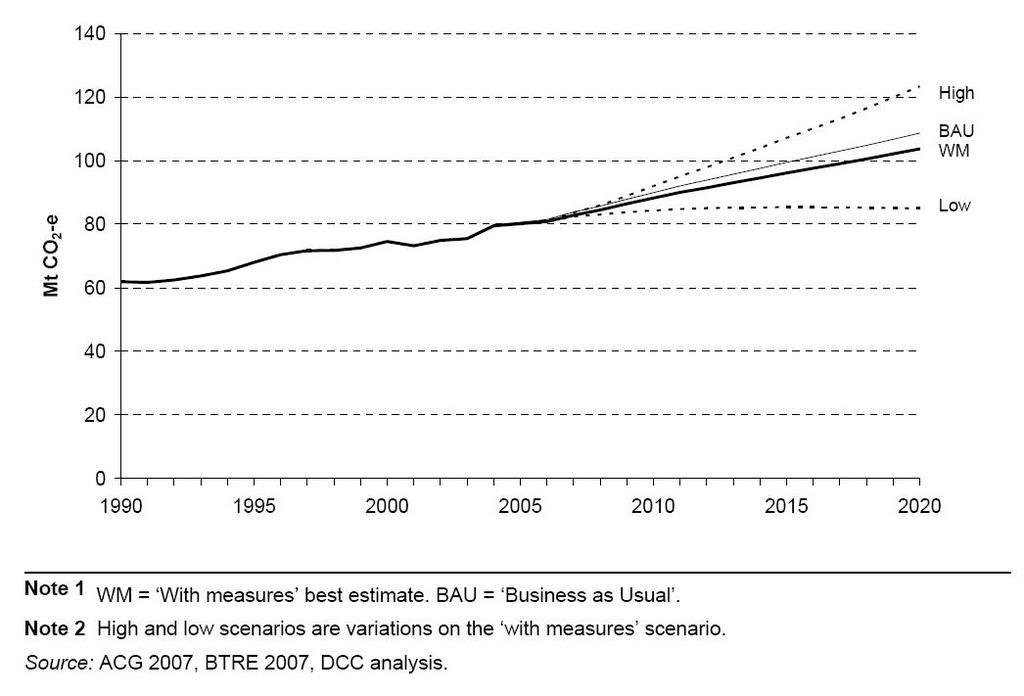

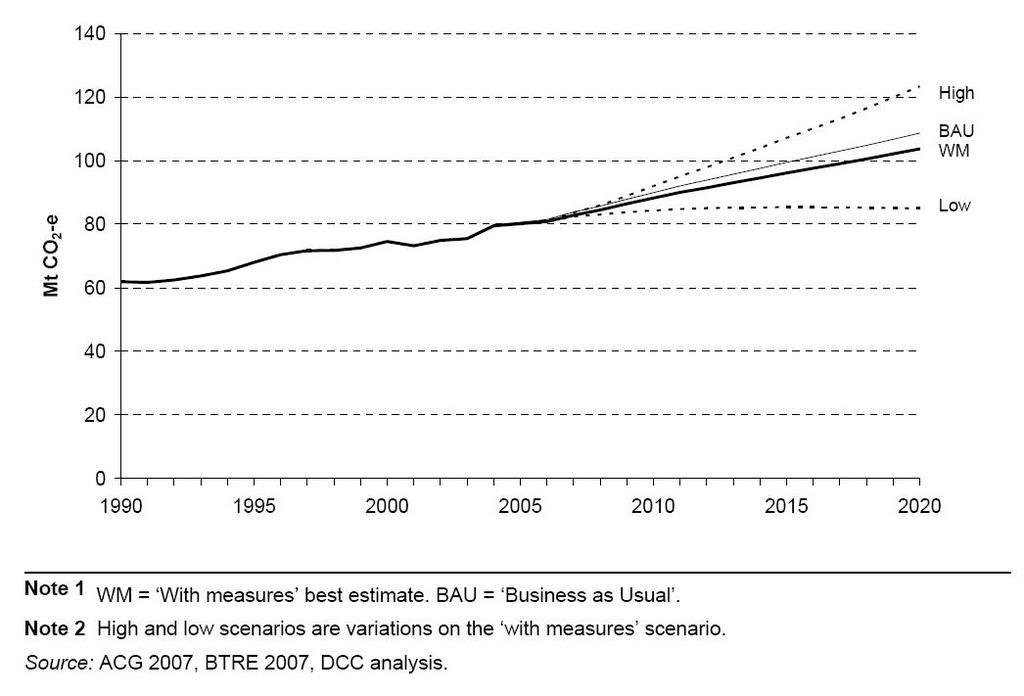

Population growth and economic growth are expected to have a major impact on the demand for transport in South Australia (and thus emissions levels). This can be seen in Figure 1 with the ‘high’ level beyond 2010 being well outside South Australian Government guidelines (WM) or even if everything else remains constant (BAU).

Figure 1 Greenhouse gas emissions for the Australian transport sector

Source: Department of Climate Change. TRANSPORT SECTOR GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS PROJECTIONS 2007, 2008, p5 | |

Theory and Research on Subsidies and Incentive Schemes:

Market forces will generate efficient outcomes only when market conditions include; the existence of perfect information, the absence of market power, the absence of externalities, and the availability of substitutes (Denniss 2003 2-3). The South Australian Government proposed incentive scheme aims to correct the market and reduce the impact of negative externalities – a cost associated with the production/consumption of a good or services which, has not been taken into account by either the producers or consumers - for example GHG and CO2 emissions (Rosen 2005 ch5).

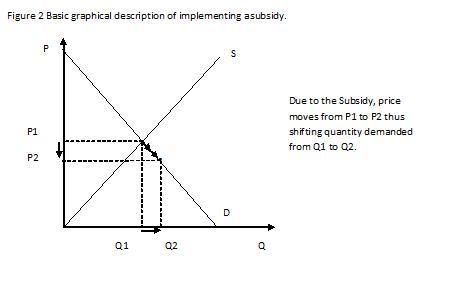

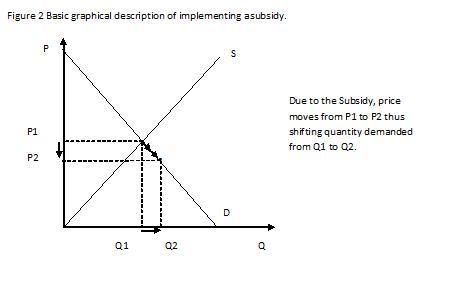

A subsidy is a form of financial assistance paid to a business or economic sector. In this specific case the subsidy in question will be a consumption subsidy given by the South Australian Government to reduce the price of HEVs such that they are more affordable to consumers and a greater quantity are sold. This theory is demonstrated in Figure 2. This assumes that the only barrier to buying a new car is the price and that there is sufficient supply to meet all new demand.

Subsidies are a direct way of achieving efficient results and previous studies (Perkins 1998) have shown that with public support they are ‘relatively successful at shifting demand’. It must be noted however that the subsidy must be large enough to create an effective incentive for consumers. Essentially, it must at least offset any price differential or perceived disadvantage of the subsidised good.

As HEVs face lower ongoing operating costs (due to lower fuel costs for the same use) (Dowling,2007) the incentive does not need to be as large as might be expected. This assumes that the consumer is both rational and long sighted. Gleisner (2006 84-85) gives the example of a NZ$7000 subsidy for the purchase of the hybrid Toyota Prius resulting in a cost differential of NZ$1270, in favour of Prius purchasers over a ten year period.

A difficulty with the basic model described above in this scenario is the unusual nature of the supply side. Many of the hybrid car manufactures make a loss producing HEV’s (Michaels 2001). Thus the quantity of these vehicles produced remains capped by the manufacturers. In the Australian market there are two dominant HEVs – the Honda Civic and the Toyota Prius. The cheaper of the two is the Honda Civic with a cap of 80 per month sold in the Australian market. The Toyota Prius is also under supply control with caps in place(Michaels 2001). Thus the question arises - will the subsidy have any effect beyond increasing demand? Michaels (2001) states that it may make production decrease further (or even stop) if a large subsidy was introduced on hybrid cars due to the fact that the more cars sold the more money is lost by the producers. Alternatively, the subsidy may allow manufacturers and suppliers to increase the price, thus decreasing their losses and increasing their willingness to supply.

A further problem with the proposed subsidy is that it does not affect behavioural patterns beyond encouraging the purchase of a more fuel efficient car. It will have no effect on how much, where and how the car is driven. This could result in more severe externalities if the consumers are not responsible drivers (through the consumers producing more emissions through longer drives, more noise and increased petrol consumption due to bad driving technique and habits) (Gleisner 2006 84-5).

Thus there is no guarantee that this subsidy will lower emissions. It is likely that an emissions reduction would occur however given the minuscule supply of HEVs, it is unlikely to be a significant reduction

Management Options for the Incentive Scheme

There are a number of variables to consider in the implementation of an incentive scheme for HEVs. United States governments have utilised a number of differing methods, ranging from free parking to Federal Government tax credits. The most effective government-sponsored incentives have been those related to income or sales tax credits (Gallagher and Muehlegger 2008).

Gallagher and Muehlegger (2008) found that sales tax incentives were more effective in increasing HEV sales than income tax credit. This is likely due to the delayed nature of the income tax credit, thereby requiring the consumer to have the rebate amount available prior to purchase. Whereas a sales tax credit may be readily applied at the point of purchase and thus effectively reduces the price of the HEV immediately.

Unfortunately, tax credits are not an immediately viable option within South Australia. As both income tax and the GST are administered by the Commonwealth Government, there is no direct avenue for South Australia to implement such a plan.

An alternative is to provide an after-purchase rebate which could be applied for by providing proof of purchase of a qualifying vehicle. A notable difference to this system is that a tax credit is limited in total cost to the government by the amount of tax that the consumer is actually paying, whereas the full amount of a rebate would be payable in all cases. Whilst this may cost the South Australian Government more (assuming equally sized rebates) it is likely that the effect of such a rebate would be greater than an income tax credit (though less than a sales tax credit). This is for two main reasons. Firstly, the dollar value of the rebate will be higher for those consumers who will be paying an amount of tax less than the full-value of the rebate. Secondly, a system such as this will be more readily understandable by consumers.

An alternative to providing an after-purchase rebate directly to consumers would be a contribution towards the purchase price of the vehicle which would be paid at the time of purchase directly to the supplier. This would effectively reduce the up-front price of the vehicle for the consumer, functioning (from an incentives viewpoint) much as a sales tax credit.

As well as considering how the price-incentive is to be applied, it is also necessary to consider the size and variability of the incentive. The United States Federal Government HEV incentive currently pays between US$650 and US$3150 dependent on the fuel economy and emissions for each model of vehicle.

If the purpose of the incentive is to promote the use of environmentally-friendly vehicles and reduce overall GHG emissions, then a structure whereby vehicles with lower emissions and superior fuel economy are more strongly supported would be ideal.

The exact dollar-value of the optimal incentive will be difficult to determine. To promote an efficient market it needs to capture the difference in the external effects of fuel economy and emissions from HEVs and non-hybrid vehicles. It is also important to consider the need to promote adoption of the new technology as the lack of support infrastructure and imperfect consumer information will negatively impact the adoption of HEV technology. The support infrastructure may include a lack of availability of spare parts and appropriately qualified mechanics to maintain the vehicles. Imperfect consumer information can lead consumers to be wary of the new technology and possibly distrust or refuse to utilise such technology.

Alternatives to the HEV Incentive Scheme

It is important to consider the primary goal of increasing HEV use.

We believe that the aim of the State Government is more related to decreasing the negative environmental effects of personal transport than to increase HEV sales or to speed the adoption of HEV technologies. As such, it is important to consider alternative mechanisms for achieving this goal.

The principle advantage of increasing the use of HEVs is the significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. HEVs do still produce GHG emissions and thus still force a negative externality upon society. It is counter-intuitive to reward an action that still produces a negative externality. We believe that it would be more efficient to internalise the cost of the environmental impacts of all vehicles in their operating costs. An obvious way to do this would be through the inclusion of petrol in the Federal Emissions Trading Scheme. This will still lead to a stronger incentive to switch to HEV-technology than currently exists as the increased cost of fuel would have a greater impact on non-hybrid vehicle operating costs than it would on HEV operating costs.

Another alternative would be to partially capture emission costs through vehicle registration fees. As emissions are largely dependent on distance travelled, and registrations costs are fixed by time, this will not be a perfect solution. However, ensuring that less environmentally friendly vehicles will face a higher registration cost now and into the future will provide further (potentially quite strong) incentive to switch towards HEV-technology. A superior option would be to link costs directly to the type and quantity of driving. In part this can be accomplished through increasing the fuel costs, but this fails to capture the differing emissions level of different cars burning the same quantity of fuel under the same conditions. A per-kilometre charge built in to registration fees would overcome this, but is not a practically viable option at this time.

It is important to consider the equity effects of non-rebate based schemes. Access to personal transport is essential in many parts of South Australia and increasing the costs associated with the majority of vehicles will have a disproportionately large impact on poorer groups. It is especially important to consider that older cars, such as those found in the second-hand market, are generally less environmentally-friendly. As such low socio-economic groups who rely predominantly on older cars will face an even greater increase in costs than the average consumer. This could have significant welfare implications and it would be necessary to examine counter-measures to this impact.

Denniss (2003) suggests other ways to reduce the emissions and other forms of transport related pollution that can be undertaken on the state level instead of a cash subsidy:

· Provide free parking to owners of vehicles with a low environmental impact.

· Tax fuel inefficient vehicles or Make petrol more expensive for fuel inefficient vehicles, thus changing the buying and driving behaviour of drivers.

· ‘Cap and trade’ for parking spaces introduced in the CBD and other congested areas.

· Abolish mobile billboards.

· Deregulate the taxi industry to lower prices and increase peak hour taxi numbers.

· Allow public transport authorities to sell a combined lottery-transport ticket, thereby increasing patronage and generating additional funds for investment in new public transport infrastructure.

· Subsidies public transport to a higher rate making it even more inexpensive thus increasing uptake.

Effects of the Incentive Scheme

There are three important effects of the incentive policy to consider:

· Increased usage of HEVs – Assuming that HEVs are replacing non-hybrid vehicles (as opposed to being used alongside), this will reduce total emissions. This may also assist in the adoption of HEV-technology, both through increasing research and development incentives for car-manufacturers and through providing advantages to those aspects of adoption dependent on network effects. This will be minimal in absolute terms due to the minuscule nature of the current HEV market and the lack of scope for short-term expansion of supply.

· Financial Costs to the South Australian Government – The State Government will face the full dollar-value cost of the incentive program. Though this may be offset by the decreased externalities associated with transport. This is likely to be a small amount given the miniscule size of the HEV market at present.

· Potential Impact on South Australian Car Manufacturers – Currently, no HEVs are manufactured within South Australia, whilst non-hybrid vehicle manufacture plays an important role in the local economy. A switch from the larger, less fuel efficient vehicles produced in South Australia, towards HEVs may have a significant impact on the local industry. However, given the relative sizes of the HEV and non-hybrid markets, even an unprecedentedly large increase in HEV sales would likely have minimal impact on the overall sales of non-hybrid vehicles in the short run. In the long run, vehicle manufacturers would have the time and opportunity to invest in HEV manufacturing technology.

Conclusion and Final Recommendation

An incentive scheme based on a rebate is only likely to lead to a small increase in HEV sales. Gallagher and Muehlegger (2008) found that tax incentives were associated with only 6% of US high-economy hybrid sales from 2000 to 2006.

The effect of petrol prices is likely to put further pressure on HEVs potentially resulting in more rebates being provided whilst not necessarily having a large effect. In the presence of other greenhouse management strategies – such as a national Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – it is likely that an incentive to switch towards HEVs will already exist in a far stronger form than a likely rebate could provide and without imposing a direct cost on the SA Government. From an economic theory standpoint, the main aim of an incentive scheme would be to remove the externality-driven price discrepancies. This would be more efficiently captured by including the emissions in the final lifetime price of the vehicle, likely by increasing the operating costs of those vehicles that are high emitters of greenhouse gases. Although one must consider the important equity issues that may arise through such a scheme.

One can argue that the need to promote a faster adoption of HEV technology and the supporting networks it requires (such as the presence of sufficient qualified mechanics) is a market failure best overcome through a price subsidy scheme.

If the goal is solely to reduce greenhouse emissions from the transport sector, then it is worth considering applying incentive-modifying policies to that sector as a whole rather than to select portions of the sector. This could be accomplished in a number of ways, including differential vehicle registration costs dependent on greenhouse emissions and fuel economy, or through capturing the full cost of greenhouse emissions in the cost of purchasing and maintaining a vehicle – for example, an ETS that incorporates fuel costs, or a carbon tax that is applied to fuels.

We would recommend that the South Australian Government exercise caution in the implementation of an incentive scheme for HEVs. It is likely that without significant improvements on the supply side, the subsidy would have minimal impact. Furthermore, the implementation of policies that internalise the cost of the GHG emissions are likely to increase the demand for HEV’s well beyond already insufficient supply capacities. It is our recommendation that the South Australian Government does not implement this policy but instead pursues the wide-spread internalisation of GHG emission sources not covered by the preposed federal emissions trading scheme whilst lobbying for and supporting a strong, effective and comprehensive federal ETS.

Reference List

Carr Kim(2008) Green Car Innovation Fund To Address Climate Change Challenge Ministers for Innovation, Industry, Science and Research Innovation Minister, Media Release, 13 May

Denniss R (2003) Implementing policies to increase the sustainability of transport in Australia, Proceedings of the WA: Beyond Oil conference (online)

Department of Climate Change. (2008)Transport sector greenhouse gas emissions projections 2007, Commonwealth of Australia

Dowling Josh(2007) Hybrid cars the go as fuel price rockets, The Sun-Herald, June 10,

Gallagher, Kelly Sims and Muehlegger, Erich (2008). Giving Green to Get Green: Incentives and Consumer Adoption of Hybrid Vehicle Technology. (online) http://ksgnotes1.harvard.edu/Research/wpaper.nsf/rwp/RWP08-009 [Last accessed 13/10/2008]

Garnaut, Ross (2008). The Garnaut Climate Change Review: Final Report. Cambridge University Press, Port Melbourne.

Gleisner B. B. Weaver S(2006). A. Cars, carbon, and Kyoto: evaluating an emission charge and other policy instruments as incentives for a transition to hybrid cars in New Zealand, Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 1: 81–89

Government of South Australia (2007) South Australia’s Strategic Plan 2007, Government of South Australia

Michaels Patrick J. (2001) Don't Subsidize My Car (online) May 21,

Newspoll (2008) 20/02/2008 – Importance and Best Party to Handle Major Issues, http://www.newspoll.com.au/image_uploads/0205%20Issues%2020-2-08.pdf [Last accessed on 13/10/2008]

Newspoll (2008) 29/07/2008 Climate Change, http://www.newspoll.com.au/image_uploads/0708%20Climate%20Change%2029-07-08.pdf [Last accessed on 13/10/2008]

O'Dwyer, Gerard,(2004) Emissions trade 'jobs threat'. Utility Week, 1/16 Vol. 21, Issue 3

Office of the Prime Minister(2008), , Joint Press Conference with Minister for Industry, Kim Carr and Premier of Victoria John Brumby, Interview, Toyota Motor Corporation, Altona, Melbourne, 01 July (online)<>

Rosen, Harvey S.(2005)Public finance (7th ed). Chicago, Irwin

southaustralia.biz,(2008) Investing in SA – Automotive (online)

Transport SA (a)(2002)What are Greenhouse Gases? (online) 16th August

Transport SA (b)(2002) Alternative Fuels (online)<> 16th August